Wild Thing: Everything You Need to Know About Savannah Cats

Yes, they’re the supermodel of the cat world, but do they belong in your house?

Share Article

In this article:

What is a Savannah cat?opens in new tab F1 Savannah catopens in new tab F2 Savannah catopens in new tab F3 Savannah catopens in new tab Choosing between F1, F2 or F3 Savannah catopens in new tab Savannah cat challengesopens in new tab Savannah cat FAQsopens in new tab

So, you’re thinking about getting a Savannah cat, or maybe you’re just curious to know why the long-limbed, spotty cat you’ve seen on Instagram looks like it belongs on the Serengeti Plains rather than someone’s sofa.

Part domestic cat, part wildcat, Savannahs are not your average feline companion. If you’ve fallen for their exotic looks, you’re not alone. But before you start mentally rearranging your furniture to accommodate a cat that can leap eight feet to the top of your fridge freezer from a standing start or working overtime to afford one of the UK’s most expensive cat breeds, let’s talk about the different generations of Savannah cats.

Not all Savannahs are created equal, so if you’re considering buying or adopting one of these highly coveted cats (and the responsible adult in us feels compelled to remind you that there are shelters full of just-as-loveable moggies who desperately need homes), it’s crucial to ensure that you understand and can meet their specific needs.

What is a Savannah cat? Breed characteristics overview

The Savannah cat breed originated in 1986, in Pennsylvania, USA, when Bengal breeder Judee Frank crossed an African serval with a domestic Siamese, producing the first F1 hybrid. Breed development took place during the 1990s, and the Savannah was officially recognised by The International Cat Association (TICA) in 2021.

It’s easy to see why Savannahs are the supermodels of the cat world; rangy with a slender physique and strong bone structure. According to the breed standard, the cats should be tall, lean and graceful with long legs and necks, tall ears, a triangle-shaped face with a tapered muzzle and slightly hooded eyes. Their short, dense coat can have striking dark spots on a background of any shade of brown (black) spotted tabby, silver spotted tabby, black or black smoke. Distinctive ocelli marks on the back of the ears are ‘desirable’.

Savannah cats are categorised by filial generations; F1, F2 and F3. These categories indicate how far the cat is removed from its wild ancestor, the African serval. F1 means that one parent is actually a serval, F2 means a grandparent was a serval, F3 means a serval was a great-grandparent, and so on. With each generation, the percentage of serval in the cat reduces, making the cat in question more like a domestic cat and less like its wild ancestor in size, instincts and behaviour.

In fact, The Cat Group (a coalition formed of Battersea, Cats Protection, the RSPCA, PDSA, BSAVA, International Cat Care and the Governing Council of the Cat Fancy) and DEFRA have recommended banning the breeding of domestic cats with F1 or F2 hybrid cats in the UK.

They’ve also recommended banning the importation of any hybrid cat except F5 Bengals or later. The Animal Welfare Committee (part of DEFRA) found thatopens in new tab, “hybrid cats less than five generations removed from the wild cat are considered the most at risk from welfare problems when kept as domestic pets”.

Let’s have a look at the characteristics of each generation of Savannah cat.

F1 Savannah cat

Appearance

The size of first-generation Savannah cat crosses varies considerably, but they average 10.5kg in weight and 16.5 inches in height. They have the most serval-like appearance, often sporting golden-coloured coats with well-defined inky black spots.

Home requirements

F1s require a specially built enclosure with secure double door entry to prevent escape, a large outdoor space with platforms to climb and a heated indoor area.

Temperament and behaviour

They have a strong prey drive, can be independent, shy and aloof. Highly territorial, they may struggle to form affiliative bonds with other cats. Uniquely, early generation Savannahs will make distinctive chirping vocalisations when they are happy or excited – a trait carried over from their wild ancestry.

Lifespan and health

F1 Savannahs tend to have shorter average lifespans than later generations, typically around 12–15 years. Having 50 percent serval DNA may make them more prone to certain health issues or stress-related illnesses, especially if their needs aren’t fully met in a domestic environment.

Cost

F1 kittens can cost as much as £20,000 due to the difficulty of successfully breeding them. Servals and domestic cats have different gestation lengths, so pregnancy complications and stillbirths are common.

Legal considerations

An F1 Savannah cat is considered a wild animal under the Dangerous Wild Animals Act 1976. It is illegal to own one in the UK without a Dangerous Wild Animals (DWA) licence, adhering to strict housing, safety and welfare requirements and submitting to regular inspections by your local council. In the United States, F1 Savannah cats are (somehow!) legal to own without a special permit in over half the states.

F2 Savannah cat

Appearance

A touch smaller than an F1, standing around 14.5 inches tall and weighing an average of 6.8kg. Their features look slightly less serval-like.

Home requirements

F2s can live inside the house, but are extremely active, agile and need plenty of space and stimulation to prevent them from becoming bored or frustrated.

Temperament and behaviour

High energy levels, a strong prey drive, and a tendency to bond with one or two people while being cautious of strangers.

Lifespan and health

F2s often live between 13–16 years. While generally considered a robust breed, they can be prone to genetic and hereditary conditions including, histiocytoid cardiomyopathy, a form of heart disease; erythrocyte pyruvate kinase (PK) deficiency, an inherited blood disorder that can cause lethargy, weight loss, jaundice, and abdominal swelling; and fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, a rare but debilitating disease where soft tissue gradually turns to bone, leading to pain, mobility loss and a shortened lifespan.

Cost

From £800 to upwards of £5,000.

Legal considerations

Currently, there are no legal restrictions on owning F2 Savannah cats in the UK and in most states in the United States.

F3 Savannah cat

Appearance

Similar in size to a Maine Coon, with an average weight of 6kg and height of 13.5 inches. As the influence of their serval ancestry becomes more diluted, they exhibit a wider range of coat colours and patterns.

Home requirements

F3s also require lots of vertical space. Think: sturdy floor-to-ceiling cat trees, and secure outdoor access to allow them to engage in natural behaviours.

Temperament and behaviour

More sociable than earlier generations, often displaying dog-like behaviours, such as playing fetch or following their pet parents around. With proper socialisation, habituation and stimulation, they are generally more adaptable to domestic life.

Lifespan and health

F3 Savannah cats can live 15–20 years.

Cost

Expect to pay between £450 to £3,000, depending on the breeder, the cat’s age and lineage, and in the case of females, whether they are being sold as pets or active on the breeding register (male Savannahs are typically sterile until the F5 generation or later).

Legal considerations

Currently no legal restrictions.

How to choose between F1, F2, F3 (or later) Savannah cat

Firstly, as gorgeous and as regal as a Savannah cat may be, consider adopting one of the mixed breed cats your local shelter is caring for. We promise they are just as capable of kitty love as a Savannah (and perhaps a little easier to look after too!). If your heart is set on a Savannah cat, however, it is vital that you consider your experience, space, time and lifestyle and be realistic about the costs and practicalities of caring for a high-generation Savannah.

For example, if you love jetting off on holiday, you won’t be able to book an F1 into a cattery (and you shouldn’t have one anyway if you live in the UK), and it could be tricky to find someone experienced to care for them while you’re away. An F3+ is likely to be more social and affectionate than an F1 or F2, which are generally not lap cats and can be standoffish with children and strangers.

Challenges of owning a Savannah cat

Savannah cats are extremely active, and their athletic prowess, high energy levels, curiosity and intelligence demand substantial physical and mental stimulation, including multiple sessions of interactive play a day, food puzzles, and plenty of vertical space to encourage exploration.

Some vets may be unwilling or lack the appropriate experience to treat high-generation hybrids, and they are likely to require specialist exotic animal insurance. Savannahs also have specific dietary requirements. Many breeders recommend a raw food diet, which can be costly and require careful preparation due to the potential for contamination with harmful bacteria such as salmonella, campylobacter, and E. coli, which can cause serious illness in pets and people.

A cat’s temperament is strongly influenced by genetic heritabilityopens in new tab from both parents, so hybridisation is unpredictable in terms of whether the kittens retain serval-like behaviours, such as territorial urine spray-marking, house soiling, inter-cat aggression, or human-directed aggression. These are commonly-cited reasons for relinquishment, re-homing or euthanasia, and while there is limited Savannah-specific research, these problem behaviours are known to be prevalent in other more established hybrid breedsopens in new tab, such as Bengals, and may be indicative of poor welfareopens in new tab.

Are Savannah cats dangerous?

Savannahs aren’t generally considered a danger to humans, though there have been reports of attacks on childrenopens in new tab. Early generation cats are muscular with a powerful bite and may have a wilder temperament or behave unpredictably if anxious, fearful, or frustrated.

The Savannah’s strong predatory drive does pose significant danger to small pets, such as hamsters, rats, rabbits, guinea pigs and fish, and if allowed to roam freely, they’re also a threat to native wildlifeopens in new tab.

Final thoughts: F1 Savannah cats

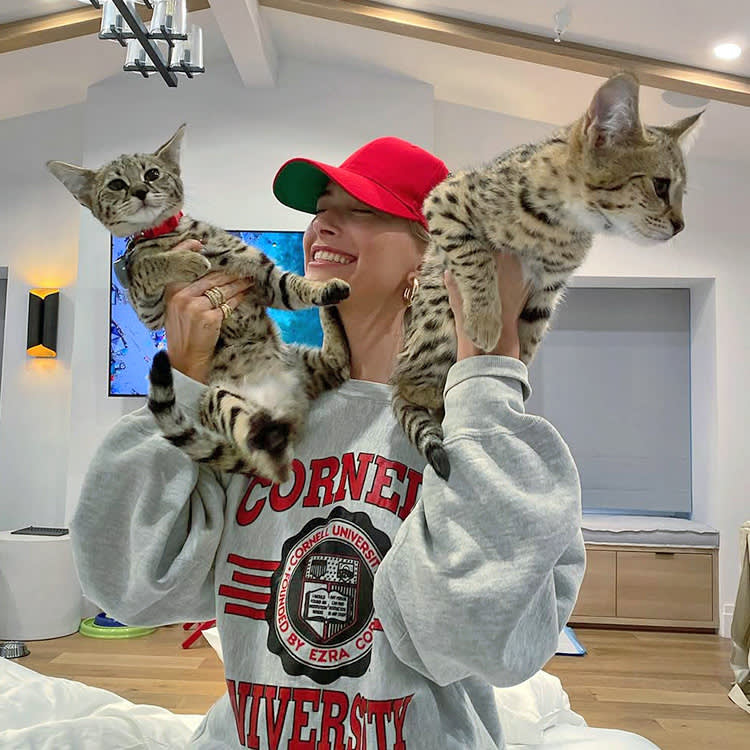

There’s no denying the allure of an F1 Savannah cat. Unsurprisingly, these show-stopping cats have become a social media sensation – Justin and Hailey Bieber’s F1 cats Tuna and Sushi had their own Instagram accountopens in new tab with over 270K followers. But they’re also a major commitment – legally, financially, and time-wise. Which might go some way to explaining why Justin and Hailey ended up apparently rehoming their reported $35,000 pairopens in new tab. In a statement that feels a little unfair considering that the couple were housing wild animals in a domestic setting, Hailey told Elle magazineopens in new tab that “the cats are amazing, but they are psycho.”

There are also valid concerns about the ethics of breeding and keeping them as companion animals. In line with many other countries, DEFRA has recently concluded that the practice is incompatible with feline welfare and responsible pet ownership, and is recommending legislationopens in new tab to ban any further deliberate breeding of domestic cats with Servals or breeding with F1 or F2 hybrids, and a ban on the importation of any Savannah to the UK.

The Cat Group (the coalition mentioned above) recently published a position statementopens in new tab highlighting serious welfare concerns relating to the keeping of hybrid cats as pets and hybrid cat breeding practices.

The Wildheart Trust’s Servival campaignopens in new tab calls for an end to the hybrid cat trade in the UK, both to prevent the suffering of hybrid and domestic cats and to mitigate against future threats to wild populations of exotic felids caught up in the ‘designer pet’ trade (there are currently 259 small and medium exotic cats or F1 hybrids registered as pets in the UK).

The UK’s primary cat registration body, the Governing Council of the Cat Fancy (GCCF), states that as a hybrid breed Savannahs are ineligible for recognitionopens in new tab because, “Outcrossing to a wild species cat brings risks (to the wild and domestic animals used for breeding, to inexperienced owners of early generations, and to the environment of the wild breed). There is no benefit to the domestic or wild cat species concerned.”

Frequently asked questions: Savannah cats

Are Savannah cats good house pets?

Later generation Savannahs – F4 and beyond – are considered more manageable in a domestic setting, but they’re definitely not for everyone. They can still be high maintenance compared to your average domestic cat and are not recommended for inexperienced cat parents.

These cats have boundless energy and intense curiosity, which needs to be channelled through environmental enrichment, interactive play and training. If they don’t have enough mental and physical stimulation, they’ll invent their own entertainment, which may well involve shredding your curtains and sofa.

They ideally need access to a secure outdoor space to allow them to exercise, explore, chase insects and run off excess energy, plus an indoor setup that gives them the opportunity to climb, jump, perch and scratch.

If their needs aren’t adequately met, their physical and mental health can be compromised, often leading to illness and/or problem behaviours.

Can Savannah cats be trained?

Absolutely, and they really benefit from it. Positive reinforcement training provides Savannahs with a predictable and rewarding way to interact with people, teaches them to become willing participants in their own care, and is a fantastic form of enrichment. These smart cats can learn all sorts of fun and useful behaviours from playing fetch to entering their cat carrier on command, though you need to find a sufficiently motivating reinforcer – usually a favourite food treat.

Savannahs are often trained to wear walking jackets so they can accompany their pet parents on outdoor adventures, but it’s important to be aware that not all cats will tolerate this. For some individuals, the feeling of restriction causes stress, anxiety or frustration.

Do Savannah cats have a friendly temperament?

As with all cats, their temperament is shaped by genetic inheritance, early life experiences, and their environment. Savannahs are known to form strong bonds with family members but may be wary around strangers. Early socialisation is vital to prevent them from experiencing fear or anxiety when encountering unfamiliar people. Later generations are generally more affectionate and often choosing to curl up next to their pet parent or perch parrot-style on their shoulders.

A Savannah is more likely to form affiliative relationships with other cats and dogs if they have positive experience with them during the sensitive period for socialisation between 2–7 weeks of age, when kittens learn what is ‘normal’ and ‘safe’.

Are F1 Savannah cats legal in the UK?

Under the UK Dangerous Wild Animals Act 1976opens in new tab, it’s illegal to own an F1 Savannah unless you hold a Dangerous Wild Animals (DWA) licence. To get one, you’ll need to be aged over 18, submit a formal application, pass an inspection of your premises by a vet and council officers, and meet strict regulations around public safety, appropriate secure housing and animal welfare standards. The cost of a DWA licence varies by local authority but can be over £650 in some counties.

What is the difference between an F1, F2, F3, F4 and F5 Savannah cat?

It’s all about ancestry. The ‘F’ stands for filial, and the number denotes how many generations a cat is removed from the serval, so an F1 Savannah is the first-generation offspring of a serval mated with a domestic cat, an F2 has a serval grandparent, an F3 a serval great-grandparent, and so on, with cats becoming more domesticated with each generation.

Is there such a thing as an F6 Savannah cat?

Yes, an F6 is a sixth-generation hybrid, usually with less than three percent serval DNA, though percentages are estimates, as if later-generation Savannahs are bred back to higher-generation individuals (a process known as ‘outcrossing’), it can bump up their percentage of wild DNA. F6 cats are generally considered fully domestic, displaying behaviour much closer to that of other high-energy domestic breeds such as Abyssinians, Burmese and Siamese.

References

BDigital Web Solutions. “ Police Probe Mystery Cat Attack on Young Boy.opens in new tab” Knews.com.cy, 2022. Accessed 27 May 2025.

Dickman, Christopher R., et al. “ Assessing Risks to Wildlife from Free-Roaming Hybrid Cats: The Proposed Introduction of Pet Savannah Cats to Australia as a Case Studyopens in new tab.” Animals, vol. 9, no. 10, Oct. 2019, p. 795.

GOV.UK. “ The Dangerous Wild Animals Act 1976opens in new tab (Modification) (No.2) Order 2007.” Legislation.gov.uk, 2011.

Martos Martinez-Caja, Ana, et al. “ Behavior and Health Issues in Bengal Cats as Perceived by Their Owners: A Descriptive Studyopens in new tab.” Journal of Veterinary Behavior, vol. 41, Jan. 2021, pp. 12–21.

McCune, Sandra. “ The Impact of Paternity and Early Socialisation on the Development of Cats’ Behaviour to People and Novel Objects.opens in new tab” Applied Animal Behaviour Science, vol. 45, no. 1-2, Oct. 1995, pp. 109–24.

Millsopp, Sarah, et al. Association of Pet Behaviour Counsellors Annual Review of Casesopens in new tab, 2012 APBC Acknowledgements. 2014.

“ Opinion on the Welfare Implications of Current and Emergent Feline Breeding Practices.opens in new tab” GOV.UK, 2024.

“ Savannah - TICA - the International Cat Associationopens in new tab.” TICA - the International Cat Association, 25 Sept. 2024.

“ Savannah Cat Sizeopens in new tab.” Savannah Cat Association.

“ SERVIVAL | the Wildheart Trustopens in new tab.” Wildheart Animal Sanctuary, Isle of Wight, 3 Mar. 2025.

“ The Cat Group Position Statement on Hybrid Catsopens in new tab.” Icatcare.org, 2025. Accessed 27 May 2025.

“ Unrecognised Breeds.opens in new tab” The Governing Council of the Cat Fancy.

Claire Stares, BA (Hons), MA, PG Dip Clinical Animal Behaviour

Claire Stares is a feline behaviourist with a PG Diploma in Clinical Animal Behaviour from the University of Edinburgh Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies. She’s dedicated to helping guardians and their cats overcome behavioural problems and thrive so that they can enjoy life together. A cat lady since babyhood (her first word was cat!), she has over 20 years of experience living and working with cats in homes, rescue environments and veterinary practices. A passionate advocate for training cats for enrichment and cooperative care, she practices what she preaches with her five cats: three rescued Domestic Shorthairs, Bimble, Bertie and Katie, a Siamese called Daisy Mae, and a Maine Coon named Horatio. When there isn’t a feline companion asleep on her laptop, she writes books and articles for various publications.

Related articles

![A bengal cat looking at the camera]()

From Bengals to Blues: The UK’s Most Expensive Cats Revealed

Meet the felines worth their weight in gold

![Newfoundland dog in the arms its owner]()

The Most Expensive Dog Breeds to Insure (How to Reduce Your Pet Insurance Premium)

How to get that insurance premium down (without sacrificing your pup’s health)

![two bonded kittens snuggling]()

Why You Should Adopt a ‘Less Adoptable’ Cat

Here’s why bonded kitties, senior cats and felines with FIV make just as amazing pets as any other

![A hand reaching towards a cat peaking out of a cage.]()

10 Questions to Ask a Rescue Centre About an Adoptable Cat

From medical history to adoption fees to litter preferences, here’s everything you need to know

![Blonde woman with hand tattoo kissing her gray kitten]()

A Step-by-Step Guide to Adopting a Cat

From where to begin looking to how to prepare your home for the new arrival